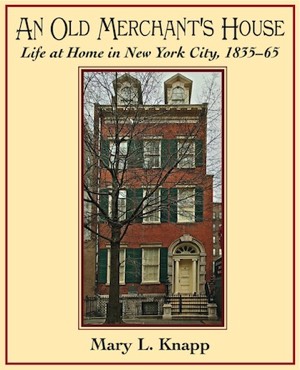

An Old Merchant’s House

Life at Home in New York City, 1835–65

by Mary L. Knapp

This book offers an authentic view of the domestic life of privileged New Yorkers in the three decades before the Civil War. It is based on memoirs, diaries, letters, and a preserved antebellum home belonging to the same family for almost 100 years. The daily life and habits of that family and their neighbors are revealed in detail.

Life at Home in New York City, 1835–65

by Mary L. Knapp

This book offers an authentic view of the domestic life of privileged New Yorkers in the three decades before the Civil War. It is based on memoirs, diaries, letters, and a preserved antebellum home belonging to the same family for almost 100 years. The daily life and habits of that family and their neighbors are revealed in detail.

Purchase An Old Merchant’s House

Excerpts:

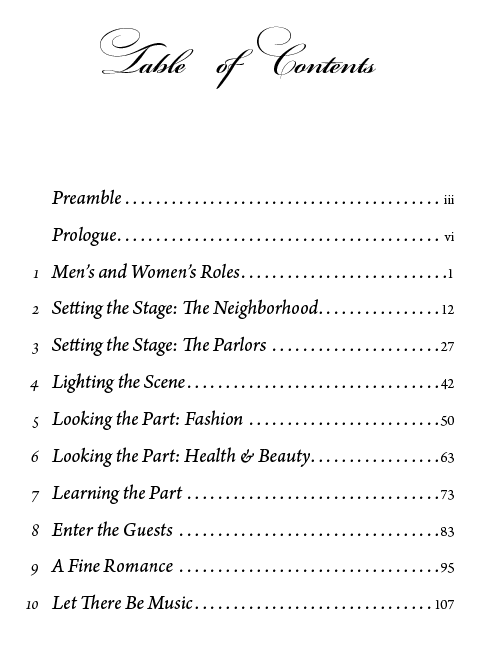

Table of Contents and

excerpt from Chapter Six: “Health and Beauty”

excerpt from Chapter Six: “Health and Beauty”

Loading...

Hair care relied heavily on the hairbrush. Lola Montez, author of a widely read 1858 advice book and herself a great beauty, recommended ten minutes brushing, two, three, or even four times a day.

Washing long hair was a major undertaking, particularly before the introduction of running water.

However, it was generally felt that it was not so much the hair that needed frequent washing but just the scalp, which may have made the job somewhat easier, even it did not make the hair cleaner. Alcohol-based hair washes were sometimes relied upon to remove the perfumed pomades or hair oils that were popular. Godey’s Lady’s Book offered a recipe for one such pomade, which was said to ward off gray hair. It consisted of four ounces of hog’s lard, four drams of spermaceti (the oil from the sperm whale), and four drams of bismuth (an alkaline metallic power) to which perfume could be added if desired. The mixture was to be applied whenever the hair required dressing.1 For washing the hair, some advisers recommended cold water only—no soap; others recommended castile soap and water.

Curls framing the face could be achieved by means of a curling iron heated over a candle flame or with “curling papers” or papillotes. These were homemade triangles of paper shaped “like the corners of a handkerchief.” A tress of hair was placed over the paper with the ends of the hair over the point of the triangle. Both hair and paper were then rolled up together and the corners of the paper were twisted tight over the curl. This was easier said than done. Yet many women slept in these papers. In 1859 a metal curler clasp was invented that was easier to use but less comfortable to sleep in. At night women typically braided their long back hair in a loose single pigtail to keep it from tangling during sleep.

_____________

1 Godey’s Lady’s Book, 59 (October 1859): 338.

Washing long hair was a major undertaking, particularly before the introduction of running water.

However, it was generally felt that it was not so much the hair that needed frequent washing but just the scalp, which may have made the job somewhat easier, even it did not make the hair cleaner. Alcohol-based hair washes were sometimes relied upon to remove the perfumed pomades or hair oils that were popular. Godey’s Lady’s Book offered a recipe for one such pomade, which was said to ward off gray hair. It consisted of four ounces of hog’s lard, four drams of spermaceti (the oil from the sperm whale), and four drams of bismuth (an alkaline metallic power) to which perfume could be added if desired. The mixture was to be applied whenever the hair required dressing.1 For washing the hair, some advisers recommended cold water only—no soap; others recommended castile soap and water.

Curls framing the face could be achieved by means of a curling iron heated over a candle flame or with “curling papers” or papillotes. These were homemade triangles of paper shaped “like the corners of a handkerchief.” A tress of hair was placed over the paper with the ends of the hair over the point of the triangle. Both hair and paper were then rolled up together and the corners of the paper were twisted tight over the curl. This was easier said than done. Yet many women slept in these papers. In 1859 a metal curler clasp was invented that was easier to use but less comfortable to sleep in. At night women typically braided their long back hair in a loose single pigtail to keep it from tangling during sleep.

_____________

1 Godey’s Lady’s Book, 59 (October 1859): 338.

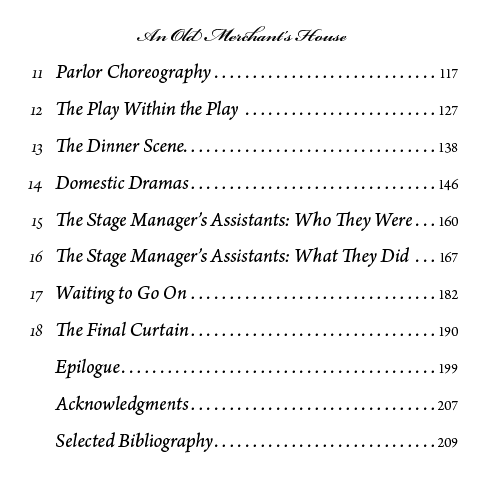

A Tredwell sister, c. 1860 from An Old Merchant's House Chapter 6, p. 69

One of the Tredwell sisters (probably Julia) reveals hair that had not been cut for years. It is likely that the photograph was taken to commemorate her appearance as the Biblical Ruth in a tableau or parlor theatrical.

One of the Tredwell sisters (probably Julia) reveals hair that had not been cut for years. It is likely that the photograph was taken to commemorate her appearance as the Biblical Ruth in a tableau or parlor theatrical.

Women who had superfluous hair above their lips or on their arms or chins or who had unattractive bushy eyebrows could, of course, resort to plucking or shaving (with a straight razor) or cutting with scissors, but they could also buy depilatories at the druggist’s, and there were numerous suggestions for caustic homemade preparations that would do the job, painful though their application and removal might have been.2

_____________

2 Virginia Mescher, an adviser to Civil War reenactors, combed contemporary sources offering beauty advice on the use of cosmetics and recipes for homemade preparations. Her study, Powdered, Painted, and Perfumed: Cosmetics of the Civil War Period and Their Historic Context (Burke, Virginia: Vintage Volumes, 2003) is available from www.raggedsoldier.com/newbooks.html. Mescher found no mention of the need to remove hair under the arms or on the legs in the sources she surveyed.

_____________

2 Virginia Mescher, an adviser to Civil War reenactors, combed contemporary sources offering beauty advice on the use of cosmetics and recipes for homemade preparations. Her study, Powdered, Painted, and Perfumed: Cosmetics of the Civil War Period and Their Historic Context (Burke, Virginia: Vintage Volumes, 2003) is available from www.raggedsoldier.com/newbooks.html. Mescher found no mention of the need to remove hair under the arms or on the legs in the sources she surveyed.

In addition to homemade dentifrices and hair pomade, face washes perfumed lotions, pastes, and salve were often prepared by women at home with ingredient purchased at the druggist’s. Advisers warned against the use of poisonous substances like lead, prussic acid, corrosive sublimate, and caustic potash, but since there were no laws regulating their sale, they sometimes found their way to dressing tables.3 Women were also warned about the eating of harmful substances for cosmetic purposes, for example the ingestion of chalk to whiten the skin and arsenic to brighten the eyes. It is not clear how prevalent these bizarre practices were. But then, as now, the prospect of becoming more beautiful was a powerful incentive.

By the mid-1830s the earlier practice of using heavy white face paint and rouging cheeks and lips had been abandoned as a deceitful practice. Some women wore no makeup at all, but many opted for at least a dusting of face powder, and some risked a subtle application of rouge. However, by the 1850s, coinciding with the gradual change in women’s dress from the drooping silhouette and pale tints of the 1840s to widened skirt and bold colors, the use of cosmetics, particularly rouge, became more acceptable. The finest of the whitening face powders consisted of powdered “French chalk” (actually soapstone). Some powders, marketed as “pearl powders” contained heavy metals like bismuth, which had the disadvantage of not only being toxic but of turning black when exposed to sulfurous gases. On occasion, such gases escaped from gas lighting fixtures of the period, causing ladies who were wearing pearl powder considerable embarrassment.

_____________

3 Ibid. 240

By the mid-1830s the earlier practice of using heavy white face paint and rouging cheeks and lips had been abandoned as a deceitful practice. Some women wore no makeup at all, but many opted for at least a dusting of face powder, and some risked a subtle application of rouge. However, by the 1850s, coinciding with the gradual change in women’s dress from the drooping silhouette and pale tints of the 1840s to widened skirt and bold colors, the use of cosmetics, particularly rouge, became more acceptable. The finest of the whitening face powders consisted of powdered “French chalk” (actually soapstone). Some powders, marketed as “pearl powders” contained heavy metals like bismuth, which had the disadvantage of not only being toxic but of turning black when exposed to sulfurous gases. On occasion, such gases escaped from gas lighting fixtures of the period, causing ladies who were wearing pearl powder considerable embarrassment.

_____________

3 Ibid. 240

Rouge could be used to color lips as well as cheeks, and like face powder, was widely available in the shops. It came in the form of powder, pomade, liquid, or pieces of gauze or silk that had been saturated with color. Eyebrows might be darkened with a pomade made especially for this purpose or with burnt cork.4 To enhance her décolleté when wearing a ball gown, the fashionable woman might outline the veins of her neck and throat with a blue powder applied with a leather pencil.5

Even after 1850, a deft touch in the use of all cosmetics was necessary, for an obviously made-up woman risked being thought of as “loose.” Whatever the antebellum woman did to enhance her looks, while not exactly a secret, was supposed to leave the gentlemen with the impression that she was a natural beauty.

_____________

4 Mescher, 50.

5 As early as 1811, a popular beauty manual condemned vein outlining. See The Mirror of the Graces (London: Printed for Crosby and Co. 1811), 56. Yet in 1869, Brinton and Napheys were recommending a blue-tinged French chalk for this purpose, and as late as 1911, aristocratic British women when preparing for a formal ball, were in the habit of outlining the veins of their throat, neck, and temple with a blue crayon. See Juliet Nicolson, The Perfect Summer: England 1911, Just Before the Storm (New York: Grove Press, 2006), 82.

Even after 1850, a deft touch in the use of all cosmetics was necessary, for an obviously made-up woman risked being thought of as “loose.” Whatever the antebellum woman did to enhance her looks, while not exactly a secret, was supposed to leave the gentlemen with the impression that she was a natural beauty.

_____________

4 Mescher, 50.

5 As early as 1811, a popular beauty manual condemned vein outlining. See The Mirror of the Graces (London: Printed for Crosby and Co. 1811), 56. Yet in 1869, Brinton and Napheys were recommending a blue-tinged French chalk for this purpose, and as late as 1911, aristocratic British women when preparing for a formal ball, were in the habit of outlining the veins of their throat, neck, and temple with a blue crayon. See Juliet Nicolson, The Perfect Summer: England 1911, Just Before the Storm (New York: Grove Press, 2006), 82.

-300dpi v3.png)