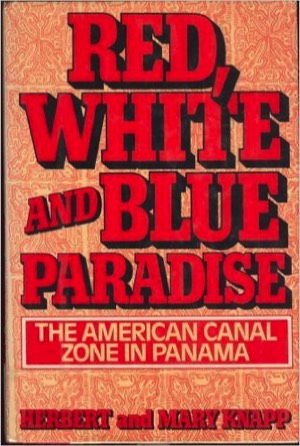

Red, White and Blue Paradise

The American Canal Zone in Panama

by Herbert and Mary Knapp

Based on our 20 years experience teaching in the former Panama Canal Zone, this book is a combination personal memoir, historical record, and sociological study of an ambiguous American utopia that existed in Panama for three-quarters of the twentieth century. Now out of print, but a reasonably priced used copy can usually be obtained from Amazon.

The American Canal Zone in Panama

by Herbert and Mary Knapp

Based on our 20 years experience teaching in the former Panama Canal Zone, this book is a combination personal memoir, historical record, and sociological study of an ambiguous American utopia that existed in Panama for three-quarters of the twentieth century. Now out of print, but a reasonably priced used copy can usually be obtained from Amazon.

Purchase Red, White and Blue Paradise

Excerpt:

From Chapter 11, “Life on the Zone: World Enough and Time”

Loading...

A Great Place to Raise Kids

What was the best thing about the Zone?” Everyone said the same thing; “It was a great place to raise kids.” The kids agreed. During the mango season, they fought mango wars, turning their battlefields to mango muck. During the rainy season, they played mud football or held skimboard contests on the sloshy grass. Secretly, they slid in the drainage ditches, which ranged in depth from a few inches to twelve feet. Parents did not approve of ditch games, especially during the rainy season. Occasionally, a child would be hurt n a ditch. Once in a great while one would be swept away and drowned. (“Et in Arcadio Ego.”)

During the dry season, children slid down grassy hills in cardboard boxes—or on what was left of the box after the first trip. They used palm fronds as play horses. They squirted each other with water from the pods of African tulip trees and burned each other with “burnie beans” that looked like eyes. (“You rub them on the sidewalk, and they get real hot.”) They watched as workmen draped a three-story wooden duplex under a canvas tent, preparing to fumigate for termites, or they fished from the bank of the Canal, thinking “long, long thoughts” as they took in the “beauty and mystery of the ships / And the magic of the sea.”

Every neighborhood gang had its hill: Clay Hill, Chalk Rock Hill, Dinky Hill, Suicide Hill, and so on. In Diablo, some children played in “the Swamp” and “the Garden of Eden.” (“Really, it was a lady’s back yard with a birdbath.”) Hummingbirds and honey creepers flitted there amid the hibiscus. Beside “the Garden” was “the Path”—a tunnel between two rows of overarching bougainvillea.

During the dry season, children slid down grassy hills in cardboard boxes—or on what was left of the box after the first trip. They used palm fronds as play horses. They squirted each other with water from the pods of African tulip trees and burned each other with “burnie beans” that looked like eyes. (“You rub them on the sidewalk, and they get real hot.”) They watched as workmen draped a three-story wooden duplex under a canvas tent, preparing to fumigate for termites, or they fished from the bank of the Canal, thinking “long, long thoughts” as they took in the “beauty and mystery of the ships / And the magic of the sea.”

Every neighborhood gang had its hill: Clay Hill, Chalk Rock Hill, Dinky Hill, Suicide Hill, and so on. In Diablo, some children played in “the Swamp” and “the Garden of Eden.” (“Really, it was a lady’s back yard with a birdbath.”) Hummingbirds and honey creepers flitted there amid the hibiscus. Beside “the Garden” was “the Path”—a tunnel between two rows of overarching bougainvillea.

At 5:15 P.M. the street lamps went on, and the children went inside for dinner. When they came back out, they played Ring-a-levio, except those who lived in Curundu. Curundu kids were ditch kids. “There’s a jungle all around there, so to get to your buddy’s house, you ran the ditches, kind of looping up one side and down, then jumping across and going up the other side. You could get a lot of momentum going.”

When the mosquito truck came by, kids ran, yelling, to hide in the plume of white insecticide trailing behind it. After that, some of them went inside. The rest gathered to tell scary stories of Tuli Vieja, searching for her lost child, or of the donkeys from construction days that were supposed to be buried under that big pile of rocks back in the jungle, or of Sal Si Puedes (“Get out if you can”), a street of shops in Panama City where children were supposed to disappear—and diners in nearby restaurants to gag, now and then, on a toe or thumb in their won-ton soup!

We asked newly arrived students what they missed most about the States. “Good TV and Big Macs.” And they complained that the Zone was “bo-ring.” We could understand what they meant. A woman who grew up there told us of the long afternoons when she and her girlfriends, for something to do, would watch the tarantulas under her house through the cracks in her bedroom floor. And certainly television and fast food were not the Zone’s strongest points. The army ran the Zone’s television station. Its ads touted the military life, United States Savings Bonds, and safety. Safety was big. One of the army’s young announcers repeatedly warned us that holes in the floor could be dangerous!

When the mosquito truck came by, kids ran, yelling, to hide in the plume of white insecticide trailing behind it. After that, some of them went inside. The rest gathered to tell scary stories of Tuli Vieja, searching for her lost child, or of the donkeys from construction days that were supposed to be buried under that big pile of rocks back in the jungle, or of Sal Si Puedes (“Get out if you can”), a street of shops in Panama City where children were supposed to disappear—and diners in nearby restaurants to gag, now and then, on a toe or thumb in their won-ton soup!

We asked newly arrived students what they missed most about the States. “Good TV and Big Macs.” And they complained that the Zone was “bo-ring.” We could understand what they meant. A woman who grew up there told us of the long afternoons when she and her girlfriends, for something to do, would watch the tarantulas under her house through the cracks in her bedroom floor. And certainly television and fast food were not the Zone’s strongest points. The army ran the Zone’s television station. Its ads touted the military life, United States Savings Bonds, and safety. Safety was big. One of the army’s young announcers repeatedly warned us that holes in the floor could be dangerous!

Even after the army station was able to transmit some news and sports events live via satellite, its programs were still chiefly of historical interest. Johnny Carson, for instance, was still telling jokes about LBJ on our screen, long after the newspapers said Nixon had resigned. Bob Cummings, Dick Powell, and Peter Lawford were smoothing their beveled haircuts and chuckling at “the girls,” while women in the States were campaigning for the ERA; and “Gunsmoke” kept coming around with planetary regularity. As for Big Macs, the closest thing to that gustatory delight on the Zone was a lumpy burger sold by the concession known as the Drive-Inn.

However, the Zone’s limitations were the other side of its advantages. When we asked the Zone kids what they missed most about the Zone when they were in the States, they told us about certain smells, the sound of rain, the feel of dry-season brisas, and of times spent at favorite places like the Causeway. On the Zone, a child woke each day to a “fruitful monotony not boredom / to be explored…”

Everywhere a child went—the pools, the libraries, the stables, the small boat ramps, the company zoo, which was located in the company’s 300 acre botanical garden—there were adults around who knew him or knew of him, and who, as a result, were inclined to look after him. We liked that. Older children sometimes found this oppressive, but it gave them a chance to know a lot of adults who were not relatives. We liked that, too.

Adults and children worked together to stage plays and parades, to organize the annual cayuco race through the Canal, to win baseball games, and to burn Christmas trees.

However, the Zone’s limitations were the other side of its advantages. When we asked the Zone kids what they missed most about the Zone when they were in the States, they told us about certain smells, the sound of rain, the feel of dry-season brisas, and of times spent at favorite places like the Causeway. On the Zone, a child woke each day to a “fruitful monotony not boredom / to be explored…”

Everywhere a child went—the pools, the libraries, the stables, the small boat ramps, the company zoo, which was located in the company’s 300 acre botanical garden—there were adults around who knew him or knew of him, and who, as a result, were inclined to look after him. We liked that. Older children sometimes found this oppressive, but it gave them a chance to know a lot of adults who were not relatives. We liked that, too.

Adults and children worked together to stage plays and parades, to organize the annual cayuco race through the Canal, to win baseball games, and to burn Christmas trees.

In some ways, Christmas was a bigger holiday on the Zone than it is in the States. Men put a giant Christmas card on the center wall of the upper level at Gatun. It offered season’s greetings in seven languages. Plywood sleighs and reindeer were displayed where passing mariners could see them. Every control tower was decorated, as were the company stores and buses. Lights were strung around houses. Some neighborhoods saw themselves in an unofficial decorating contest, but no place out-Christmased Santa Claus Lane—the folk name for a neighborhood where for years one of the residents played Santa on Christmas Day. In 1977, a teenager recalled her first Christmas in that neighborhood. She was four.

I didn’t know what it was all about until I saw this big, red sleigh in Mr. Townsend’s garage. All I could see then was a red cap and a snow white beard. When it was my turn, I was handed up to this big fat man. I can remember David got a set of cowboy guns, and I got a square box containing a white tea set decorated with little red flowers. That was the last year they did that…

-300dpi v3.png)